The March Lunch & Learn was somewhat of a history of "demics". We learned about "pandemics" (an epidemic on a global scale), "epidemics" (effecting a large number of people but not at the level of a pandemic), and "endemics" (a particular disease affecting a group of people or a country). Our presenter was Normal Erickson representing the Indiana Medical History Museum located in the near northwest side of Indianapolis. What is now the history museum was built in 1895 as a working laboratory with an amphitheater as port of the Central State Hospital and was in operation until 1956. The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Over the years the laboratory served the doctors to study and learn from the deceased patients at the hospital. Originally the patient’s preserved remains were not specifically identified, but recent re-humanization efforts have sought to connect specific patients to the specimens displayed in the museum.

The March Lunch & Learn was somewhat of a history of "demics". We learned about "pandemics" (an epidemic on a global scale), "epidemics" (effecting a large number of people but not at the level of a pandemic), and "endemics" (a particular disease affecting a group of people or a country). Our presenter was Normal Erickson representing the Indiana Medical History Museum located in the near northwest side of Indianapolis. What is now the history museum was built in 1895 as a working laboratory with an amphitheater as port of the Central State Hospital and was in operation until 1956. The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Over the years the laboratory served the doctors to study and learn from the deceased patients at the hospital. Originally the patient’s preserved remains were not specifically identified, but recent re-humanization efforts have sought to connect specific patients to the specimens displayed in the museum.

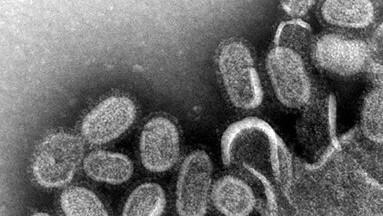

As we are currently familiar with the COVID pandemic, Ms. Erickson presented some similar history of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. This virus was later traced to swine flu origin around Fort Riley, Kansas. The fort was a training center for U.S. soldiers before shipping overseas for duty in World War I. With contact with soldiers from other countries, the virus quickly spread all over the world. A conservative estimate is that 50 million people died from the Spanish Flu. A question from one of the attendees asked, “why was it called the Spanish Flu?” Norma said during WWI, Spain was a neutral country and as such was willing to publish its flu statistics, so everyone blamed it on them!

A virus cannot reproduce itself and needs to attach to other living cells; these cells die weakening the person. In an effort to control the spread, authorities closed schools, pool halls, bowling alleys, streetcar transportation, banned gatherings, and had people wear masks. As soldiers returned at the end of the war, the pandemic continued overwhelming hospitals. Distrust of authorities and scientific information abounded.

Explaining another virus, Ms. Erickson described how the polio virus attaches to nerve cells in various parts of the body and immobilized the nervous system controlling muscular function. This virus enters through the mouth or nasal cavities. A medical device we may recall is the “iron lung” used for patients with weaking lung function. Creating a rhythmic vacuum cycle the iron lung assists the patient’s lungs to expand, facilitating breathing. The museum has a small iron lung used for children on display.

President Frankin Roosevelt initiated the March of Dimes campaign in 1938 to fund research to combat polio. It was the first campaign ever to target a specific disease. In 1955, Dr. Jonas Salk had a treatment to kill the virus. In 1961, the Sabian method used a weakened live virus treatment. This was administered to children in sugar cubes. The year 2000 saw an inactivated polio virus used as a prevention.

At the present time, the museum only has guided tours of one hour by appointment only. Senior admission is $9.00 per person. The museum is funded by admission fees and donations; there is not state funding. Parking is plentiful. The building does not have an elevator so stairs may be a hinderance. A video tour is available at www.imhm.org. Remodeling of the facility was considered at one point, but that never happened so it appears much as it did in 1895 which Ms. Erickson considers to be an asset for the history presented at the museum. She also made mention of the medicinal plant garden that has approximately 110 varieties.

Submitted by Don Diego de la Vega (AKA ?)